by Gary S. Breschini, Ph.D.

The Royal Presidio of San Carlos de Monterey is one of four presidios or military forts designed by engineer Miguel Costansó along the California coast. Other presidios were located at San Diego (1769), San Francisco (1776), and Santa Barbara (1782).

The Presidio of Monterey was founded on June 3, 1770, by Fray Junípero Serra, Gaspar de Portolá, Fray Juan Crespi, Lt. Pedro Fages, six Catalonian Volunteers, four cuera soldiers, and men from the ship San Antonio. This is described in the previous section on the founding of Monterey.

On June 4, 1770, Costansó surveyed a level spot directly in front of the ship and perhaps two gunshots from the beach, near “an inlet which communicated with the bay at high water” (Lake El Estero). The site is approximately bounded by Webster and Fremont streets between Camino El Estero and Abrego Street.

Work apparently began immediately, but the temporary church was only partially completed when it was blessed on June 14. Culleton describes how, for the feast of Corpus Christi, the square marked off for the presidio was swept clean and an altar set up for High Mass and the traditional procession.

Costansó’s plan called for a fortified square about 200 x 200 ft. (outside measurements), with an inner plaza of about 160 x 160 ft. This left a space about 20 ft. deep for buildings placed against the outer walls.

The original presidio was a stockade made of earth and pine logs. Portolá and Costansó did not stay to see the design completed–they returned to Mexico on the San Antonio on July 9, 1770. By that time the preliminary wooden palisade was probably completed enclosing the plaza. Buildings included a church, warehouse, quarters for soldiers and priests, and a powder magazine. The walls of these buildings were poles driven closely together into the ground.

Work on the more permanent adobe walls probably began immediately. By the middle of November 1770 the square was enclosed so well that Fages was no longer worried about the safety of the inhabitants.

At the presidio, building operations were probably conducted for most of the the winter and spring, as on June 20, 1771 a communication from Fages to the viceroy implies that everything was complete except for the new church, which was to replace the original brush structure.

Supplies came by ship from San Blas, but scurvy often prevented the crews from completing their supply runs. The San Antonio, which left Monterey on July 9, 1770, returned with supplies on May 21, 1771. Letters brought to Serra and Fages gave permission to move the Mission San Carlos to Carmel. The ship sailed for home on July 7, with Fages aboard. By July 9 Serra was in Carmel Valley selecting a new site of the mission. Three or four days later he was on the way to select the site for Mission San Antonio. Construction on the mission at Carmel started on August 24, and the move was made complete on December 24, 1771. By that time Fages had returned by land with 20 additional soldiers.

During 1772 the supply ship failed to arrive, and the nearly 50 men at the presidio and mission were saved from starvation by sending most of the soldiers on a massive bear hunt to San Luis Obispo County (from late May through August) and by the generosity of the Indians, who shared their food. On August 24, 1772 Fages and Serra traveled to San Diego overland in search of supplies. They were able to convince the captain of the San Antonio to sail for Monterey, and additional supplies were sent by pack train. In spite of the supplies, the garrison at Monterey and the mission at Carmel consisted of soldiers and priests, not farmers. Famine struck again in the summer of 1773–the supply ship failed to arrive again–and lasted until the spring of 1774.

Work continued on the presidio, with gradual improvement and expansion, and subsequent repair as the original walls deteriorated. In 1773 Fages noted that there were about 30 buildings inside the stockade. Those against the eastern and western wall were of pole and mud construction with sod roofs. The church and its outbuildings on the southern wall were of adobe on a stone base, as were the commandant’s quarters, jail, storerooms, and guardhouse against the northern wall. The north wall was adobe on a stone base, while the other three walls were still of earth and logs. At each of the corners was a ravelin with two embrasures and a single bronze campaign cannon. The northwest ravelin was of adobe. A powder magazine was located east of El Estero and about a mile and a half southeast (toward the airport) was a vegetable garden guarded by two soldiers who lived in a hut nearby.

On April 18, 1774, Don Juan Bautista de Anza reached Monterey, having marched with 20 soldiers overland from Sonora. This opened up a new route directly to the missions of Sonora, which had been settled for many years. Four days later he was on his way back. On May 9 the Santiago arrived in Monterey carrying supplies and seven women, six of whom remained at the presidio. Two days later Serra returned overland from San Diego, and on May 23, Don Fernando Rivera y Moncada, the new military commandant, arrived overland. The outpost was growing. From this date on, supplies arrived more regularly, both by ship and overland.

On the evening of March 10, 1776, de Anza arrived in the pouring rain, this time with more than 130 soldiers and settlers destined for San Francisco–completely overwhelming the facilities of the presidio. On June 17 they continued on to San Francisco.

On February 3, 1777, Rivera was replaced by Felipe de Neve, who from that date governed Alta and Lower California from Monterey, now the capitol of Las Californias. Rivera was posted as Lieutenant Governor to Loreto, the former capitol. (Follow this link for a list of the Spanish governors.)

By July 3, 1778, Neve had completed the conversion of the log and earth stockade to a stone and adobe wall. Inside were ten adobe buildings reported to be 21 x 24 ft. and a long barracks, nearly finished, measuring 18 x 136 ft. The new buildings were thatched, rather than roofed with sod. Now that the planned structure was largely finished, work apparently slowed.

In 1789 a salute gun ignited a thatched roof, and the resulting fire burned half of the buildings, including the entire northern side. They were not rebuilt until 1791, although some buildings were roofed with tile in 1790. The stone Presidio Chapel which stands today was built between 1791 and 1795.

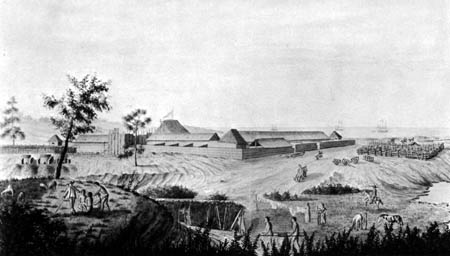

The first good drawings of the presidio come from September 1791, when the Spanish expedition under Alejandro Malaspina spent two weeks in Monterey. The José Cardero drawing of the presidio, done at this time, appears below.

In 1792, an outlying gun emplacement, called El Castillo, was built on the side of today’s Presidio of Monterey, overlooking the harbor. This is also the current site of the Serra Monument. The cannon from the presidio were moved to this location, ending the use of the presidio as a fort. From this point, the presidio became more of an administrative center and unfortified barracks.

Vancouver visited Monterey in 1792 and again in 1793, and left a description of the presidio. He also mentioned an outpost at the mouth of the Salinas River where “a small guard of Spanish soldiers are generally posted, who reside on that spot in miserably wretched huts.”

Spain established a formal pueblo government in 1791, and it went into effect in 1794. By this time, outlying cattle ranches were being established in the Salinas Valley. No grants could be made to private individuals. Rather, unneeded land could be assigned as provisional concessions. These were generally for the use of retired army veterans. As was often the case with concessions, the grantees made little effort to hold their lands. The Las Salinas concession was granted before 1795, and in 1795, José Manuel Boronda was granted the El Tucho, in the Blanco area southwest of Salinas, and José Maria Soberanes and Joaquin Castro were granted the Buena Vista, south of Spreckels. There was possibly a fourth concession, Llano de Buena Vista, along the Salinas River as well. However, local Indians, most likely the Ensen, a subdivision of the Ohlone who lived in the Spreckels and Toro areas, attacked and burned these four ranchos in 1795.

According to Bancroft, in 1800 the majority of the settlers on the Monterey Peninsula still lived either in the presidio or at the mission in Carmel, although a few people lived on outlying ranchos, such as Buena Vista and El Tucho, both south of Salinas. The population of the presidio itself was probably about 370. At the end of this year Carrillo notes that the square measured 110 yards, the four walls were built of adobe and stone, and the buildings were roofed with tiles. On the north were the main entrance, the guard-house, and the warehouses. On the west were the houses of the governor, commandant, and other officers, some 15 apartments in all. On the east were nine houses for soldiers and a blacksmith shop. On the south were nine more houses and the stone Presidio Chapel. All the structures were again in bad condition, with the walls cracking because of inadequate foundations.

In February of 1801 Governor Arillaga informed the viceroy that the presidio was “in ruinous condition.” The inability of adobe to withstand the elements, even in such a mild climate as Monterey, is evident from the reports that in March of that year the main gate of the presidio was demolished by a wind and rainstorm.

In spite of the deterioration and need for constant repair, the presidio remained the center of Monterey for a number of years after 1800, and virtually the entire population of Monterey lived within the walls. Even though the outer walls were continually expanded (reaching some 200 yards on a side), living conditions were damp, crowded and unsanitary. Monterey was an outpost, not a town. It was not self sufficient, as was the mission at Carmel, but still relied on supply ships from Mexico. The Hidalgo Revolt and the subsequent disorders (1810-1817) curtailed those supply ships, and increasingly the mission had to support the civil and military personnel. British, American, Russian, Peruvian, and other merchant ships brought supplies on an irregular basis, as most such trade was considered illegal. A visitor in 1814-1815 notes the population at about 400.

Horne notes “From 1810 to 1820 the Monterey garrison, never too well paid at best, received no pay at all. Within a period of fifty years Portolá’s royal fortress had become a forgotten outpost of a crumbling Spanish empire.” It was during this period (1818) that the presidio and fledgling town were sacked by Hipólito Bouchard, the Argentine privateer.

Beginning somewhat before 1820, a few families, led by Corporal Manuel Boronda, took up residence outside the presidio walls (a few people had lived in outlying ranchos as early as the 1790s, but these do not seem to have been permanent residences). Teresa Russell (a descendant of Corporal Boronda) notes “the Borondas were the first people to build a home outside the walls of the presidio. There had been other grants bestowed in the Carmel Valley, but none of the grantees had chosen to occupy their land. Their adobe was one room. They had an outdoor kitchen called a ‘ramada.’ They wore fine clothes in homemade surroundings.”

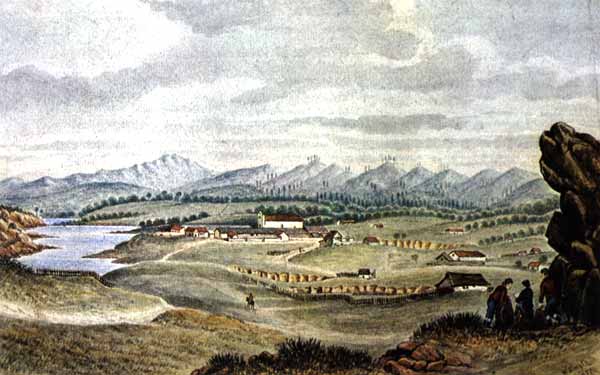

In 1814, a number of non-Spanish immigrants began to settle in Monterey. But the town grew slowly. A watercolor by William Smyth during the winter of 1826-1827 shows a small number of scattered adobes without any formal property lines, fences, or streets.

But by the early 1840s the pattern of the town was laid out and the presidio ceased to be the center of activity. After the American occupation the old presidio was abandoned and a new facility was built near the site of El Castillo, on the hill overlooking the harbor.

Copyright 1996 by G.S. Breschini

Sources:

- Bancroft, H.H., History of California, Vol. 1: 1542-1800 (Wallace Hebberd, Santa Barbara, CA, 1963; original 1886).

- Clark, Donald T., Monterey County Place Names (Kestrel Press, Carmel Valley, 1991).

- Culleton, James, Indians and Pioneers of Old Monterey (Academy of California Church History, Fresno, CA, 1950).

- Horne, Kibby M., A History of the Presidio of Monterey, 1770 to 1970 (Defense Language Institute, West Coast Branch, Presidio of Monterey, California, 1970).

- Howard, Donald M., California’s Lost Fortress: The Royal Presidio of Monterey (privately printed, 1976).

- Van Nostrand, Jeanne, A Pictorial and Narrative History of Monterey, Adobe Capitol of California 1770-1847 (California Historical Society, San Francisco, 1968).