Kodomo No Tame Ni: The Castroville Japanese School

By Sandy Lydon, Historian Emeritus, Cabrillo College

For over sixty years, the small, unassuming building standing on the corner of Geil and Pajaro in Castroville has been patiently waiting to tell its story. Some of Castroville’s long-time residents remember when it was used by Castroville Elementary School as a classroom, but the earliest history of the building, stretching back into the mid-1930s is known to only a few of the town’s oldest residents. The building and the entire block upon which it sits were recently purchased by Monterey County, and under the guidance of Jerry Hernandez and the county’s Housing and Redevelopment Department, the history of the building is finally coming to light.

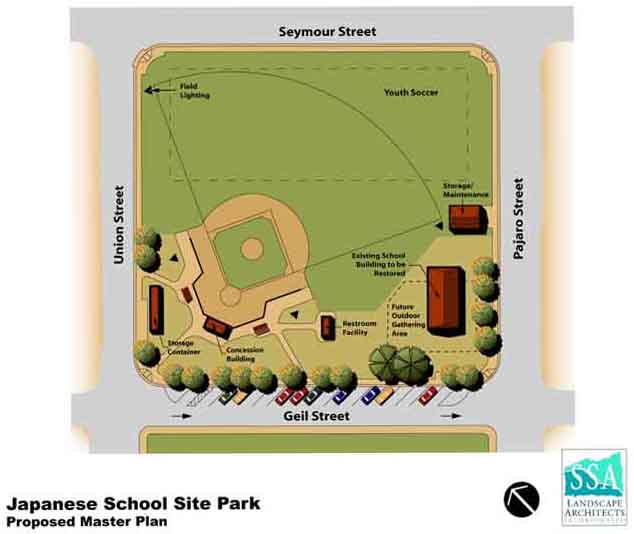

Between 1925 and 1935, the Japanese population of the Salinas Valley grew to an estimated 250 families, with 200 in the vicinity of Salinas, 30 around Chualar and 25 in and around Castroville. During these years Castroville had both a small Chinatown and Japantown. The Issei had already established a Japanese School at the Salinas Buddhist Temple, and in the mid-1930s decided to set up branches in Chualar and Castroville to serve the growing number of Nisei reaching school age. In 1935, a corporation named “The Buddhist Church of Castroville” purchased the entire block bounded by Geil, Pajaro, Seymour, and Union streets. Because of California’s Alien Land Laws, the corporation was led by Nisei, with Hiroshi Kitaji signing the original deed.

Not long afterward, the community began building the simple Japanese School building on the southwest corner of the property, and for the next six years, many of the Nisei children living in and around Castroville attended the school. Classes were held in the afternoons beginning at 3:00 PM for two hours with another half-day on Saturdays. In a recent interview, Mrs. Yoshio Matano, one of the school’s teachers, said that most of the students were young boys and that though they seemed a bit reluctant to attend class, they studied hard. The curriculum centered on the Japanese language, with other instruction covering Japanese cultural practices. The Issei parents were hoping that their children might learn some of the Japanese traditions in this school while learning about America in public school. The teachers were hired by the Salinas Buddhist Temple, and paid through the tuition paid by the Issei parents. Mrs. Matano remembers being embarrassed by the high pay of $60 per month, a high salary during the Great Depression, and she asked that the pay be reduced. One of the other instructors at the Castroville Japanese School was the Reverend Bunyu Fujimura who commuted over to the school from Salinas.

All the Japanese Schools closed immediately following the bombing of Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941. The FBI arrested Reverend Fujimura in early February of 1942 in what was at that time “the largest raid against aliens in the History of the United States.” On February 21 of that year, twelve more Castroville residents were arrested, including eight Italians who were suspected of supporting Italian fascist causes.

The school building stood vacant when the Japanese community was evacuated to the Salinas Rodeo Grounds in late April of 1942. The return to Castroville and the Salinas area following the end of World War II was very difficult, as anti-Japanese sentiment was extremely high. Housing was also in extremely short supply, so many of the families that did return to the Castroville area had to share whatever accommodations they could find. Frank Oshita remembers that the older members of his family occupied the family home, while he and other Nisei men used the Castroville Japanese School building as a bunkhouse, sleeping there at night.

Sometime following World War II, the building was acquired by the Castroville Elementary School, and slowly, over time, the building’s history began to fade away. Fortunately, however, the memories of one of the school’s early students did not fade. In the 1990s, in an effort to save and preserve the building, Mr. Kunio Sumida of Los Angeles, began a successful effort to have the building placed on the National Register of Historic Places. Being on the register gives the building considerable protection, and when Monterey County recently purchased it, they vowed not only to preserve the building, but also to restore it to its original 1930s construction.

In the past several months, historical restoration architect Glenn David Matthews has begun drawing the plans to restore the building. With the assistance of Jeff Sumida, Helen Kitaji, and Frank Oshita, a committee has been guiding the future plans for the building and the entire block. The plans are for the building to become a community center that can be used for Castroville community and non-profit organizations.

One of the committee members is Francisco Casas, the director of an organization known as Grupo Residentes De Castroville. One of Francisco’s most famous efforts has been teaching guitar lessons to many of Castroville’s Latino children. During a recent committee meeting, Francisco provided us with the theme of the Japanese School’s restoration. As he told us about how he meets with his students every afternoon and on Saturdays for practice, we realized that Francisco and the Castroville Latino parents are doing exactly what the Issei parents did for their Nisei children back in the 1930s–teaching them to have pride in the culture of their parents. Helen Kitaji remembered the oft-repeated Japanese phrase used by the Issei parents–kodomo no tame ni, for the sake of the children–and the idea for the theme of the building’s restoration was born.

All immigrant parents were concerned about the possibility that their children might completely forget the culture that they had brought with them from the old country. Chinese parents set up Chinese Schools, Italians parents had Italian language classes, and Portuguese parents sponsored Portuguese language classes for their children. Today, what Francisco Casas is doing is exactly what all immigrant parents have done–attempting to preserve a bit of the immigrant culture in the hopes that not all of it will be lost in the Americanization process.

The current plant is to have the phrase “For the Sake of the Children” as the motto for the entire Castroville Redevelopment process–for the soccer and baseball fields, for the library and museum–because, in fact, it all really is for the youth of the community. And someday, as Francisco’s students come into the afternoon guitar lessons in the restored Japanese School building, they will see the phrase in Spanish, Portuguese, Chinese, Italian, and Japanese flowing around the room above the walls, and they will see photographs of those who have come before, and like their own parents, have enriched the Salinas Valley with their sweat and blood.

If you stand outside the Castroville Japanese School in the afternoon, you can hear the wind sighing through the large pine trees that frame the building. And, if you listen closely, you can hear in all the languages, “For the Sake of the Children.” The vision of those dedicated Issei parents will live on in the building.

Note: The Directors of both the Salinas and Watsonville-Santa Cruz JACL Chapters recently endorsed the concept of the restoration of the Castroville Japanese School.

Sandy Lydon is the historian working with the Redevelopment Agency to research the Castroville Japanese School’s history. The author of The Japanese in the Monterey Bay Region, Lydon was the receipient of the JACL’s Creed Award for his work in helping in the redress effort in the 1980s. He is a member of the Watsonville-Santa Cruz JACL.